Many years ago I found a very wise principle called DRY. This is an acronym for Don’t-Repeat-Yourself. It’s easy to see why repeating behaviour around a code base will make it rigid to change. The outcome of doing DRY is that we end up with a lot of abstractions that can be shared between projects. In this post we will examine how Domain Driven Design can help us pick the best way of sharing code between our projects.

The value of simple procedural code

There is a book that I like very much called “Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code” by Martin Fowler and Kent Beck. This book will show you some smells and how you can refactor them using design patterns and this is great but this is not what I like the most about this book. The best part of this book for me is when they teach you how to think. My favourite part is when they discuss the right moment of introducing a design pattern. They propose that code repetition is the foundation of all abstractions. This is because repeated code indicates the right moment of when to jump from the simplest procedural code to an abstraction. I believe this book was written in the 1990s before TDD was invented so if you are doing proper TDD i.e the simplest code that will make the test pass then this should be happening naturally. The problem of introducing design patterns head on is that usually, it overcomplicates what could have been a simple, elegant, intention revealing solution.

Now if you did all of the above correctly you should then be getting some repeated code. How should you DRY it? This is where Domain Driven Design can help you. In DDD there is a concept of a Cross-cutting concerns and Core concerns. In the rest of this post we will look at both of them.

The Good: drying Cross-cutting concerns to NuGet packages

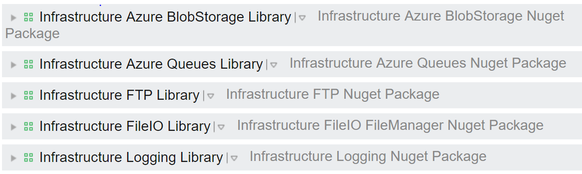

They are the concerns that are shared throughout the application. They are most likely technical tasks and this is where having shared libraries with their own release pipeline can work really well.

When I joined my past employer the first task that I picked up involved changing how Logging was performed. Now tweaking Log4net was easy. The hard part of distributing the changes to some 20 projects. This is when we created a NuGet package that could be easily distributed and versioned. We ended up creating more of these packages and other teams started using and contributing to them. Alas identifying our cross-cutting concerns was very helpful to us.

Below is how our pipeline looked like:

The Bad: drying Core concerns to shared libraries

Core concerns are the problem your domain is trying to solve. It’s usually a bad idea to extract them to shared libraries and distribute them via project references or NuGet packages. An example of this would be an imaginary insurance company where customers can get a quote through a website or through an automated telephone system. The quote must be the same on both systems. We can see a solution to this being a “Calculator” class library that is referenced on both systems.

The problem with this approach is that if the calculation of the quote changes then we must coordinate both systems to be released at the same time. This is where having an API providing a single source of truth would come useful.

Usually a smell of this approach is when a solution has a class library called “Core.Domain”.

The Ugly: drying any kind of concern to base classes

The easiest way to explain inheritance versus composition is to understand the difference between frameworks and libraries… and the difference is Inversion of Control. When using a framework, the control of the application is being delegated upstream and this is exactly what base classes do. Usually base classes are designed with some of its methods open to be overridden. The problem is these methods are usually coupled to some other methods of the base class that there is no visibility of and then the flow of control is going up and down. This is very bad for when trying to understand the intention of the application and for testing.